July 2023

Vineyard tending took a few days off in early July due to a long Independence Day weekend and family visits. Covered in June’s Chronicles, the previous month was filled with keeping vines pruned and growing vertically, and remaining abreast of insects and critters determined to ruin my day. Invaders aside, as July progressed the vines remained healthy exhibiting strong growth. Grape clusters asserted themselves. Witnessing cluster growth in this third season was new and exciting. The first two seasons of vine growth mandated the removal of grape clusters as they appeared since a plant’s energy should go towards vine and root development, not fruit.

We shouldn’t begin our earnest review of July’s vineyard activities without first acknowledging the valley’s big event around Independence Day. Usually by early July cherries are ripening in the valley. This occurrence has been heralded for the past 77 years by the Paonia’s Cherry Days Festival—Colorado’s longest-standing community festival. Always convened July 3 and 4, the festival bursts with vendors, food, drink, and kid activities in Paonia’s town park. Independence Day celebrations kick off with a parade in the morning down Grand Ave, concluding at the park where family and friends gather in groups under the shade to picnic and enjoy each others’ company for the remainder of the day. Our family took advantage of it all, thoroughly enjoying ourselves. You’ve never experienced small-town America until you spend time with familia at the Paonia Cherry Days Festival.

I realized after the holiday the Riesling vines required attention due to their tall growth above the top trellis wires. They were hanging over the top of the trellis, significantly shading the plants and putting the upper vines at risk of being cut by the wires during windy periods. I could “hedge” the tall vines, cutting them above the trellis wire at approximately six feet. A disadvantage of hedging is the promotion of lateral (versus vertical) vine growth within the leaf canopy. Lateral growth results in a tangled mess of the canopy, restricting light and airflow diminishing fruit quality, and promoting mildew should extended wet conditions occur. Excess lateral growth can also interfere with netting, which is normally installed as the grapes ripen and take on higher levels of sugar—of great interest to birds. As an alternative to hedging, adding a pair of wires at the top of the posts bringing the total trellis height to seven feet, could provide the vines with extra vertical growth space. Adding another pair of wires to accommodate the growth moved to the top of my to-do list.

As June illustrated, you know good and well that we couldn’t work through another month in the vineyard without new pest activity. One pest was obvious, grasshoppers. Walking between the rows, they’d jump in and out of the leaf canopies, having had their snacking disturbed. Leaves were their primary target, no interest was shown in the developing grapes. The other potential pest was sucking the life out of small groupings of grapes within a larger cluster. A small group of grapes would begin to shrink, and eventually dry to small hard berries. As a rookie I immediately panicked, thinking all the clusters vineyard-wide would be destroyed.

I decided to take a wait-and-see attitude toward the grasshoppers. The first week or two of leaf damage seemed quite nominal. A friend recommended mixing water and molasses in a 10 to 1 ratio, placing the concoction in tubs under the vine leaf canopies. In theory, grasshoppers would gladly partake and drown in the sticky excess. No such luck, though a few may have accidentally drowned due to an errant jump. Over the course of the month, leaf damage was evident but not in a manner crucially affecting vine health. I remained watchful, killing a few as I came across them but taking no further action.

However, there was a predator taking action. Vineyard lizards, which have been bountiful in the vineyard as of late. Coming across a lizard one morning with a grasshopper in its maw gave cause for celebration.

With research and talking to my grower mentor regarding shriveling and dried berry groupings, it became clear the condition was common but the potential causes were many. And no, the issue wasn’t necessarily going to run rampant and destroy all the grapes.

Potential non-biological culprits were excess heat or lack of water, causing the petiole to die. Knowing these potential causes hadn’t been an issue to date, I closely examined the petioles and leaves. Petiole deaths were not my issue.

Another culprit was sour rot, caused by damage from fruit flies, yellow jackets, or other pests. One of those pests is earwigs (ew), which like to hang out in choice clusters using their little pinchers to enrich themselves and do damage. I visited my mentor’s vineyard, and we found a few earwigs behind drying berries on his clusters. As an organic grower, he uses diatomaceous earth (DI) as a control. He applies DI up and down the rows along the grape clusters. Over a day or two earwigs (and other pests if they’re so inclined—including grasshoppers) keep munching eventually ingesting the DI. DI acts to dehydrate the insect, often fatally. Back in my vineyard, I could find no earwigs or other pests.

The last potential issue was black rot, which thrives in wet and humid conditions. I had already sprayed three times for mildew and the past two and a half months had been very dry. There was no evidence on the vines and leaves. Black rot it isn’t.

The bottom line, the cause of this issue remains a mystery. My solution involves removing dried berries as I come across them, and for the time being, all is well.

Speaking of earwigs (ew), I came across them when harvesting apricots. There are half a dozen apricot trees on the property and I was bound and determined to process them into preserves. The task was accomplished to the tune of 36 half pints. Preserves for everyone!

For the remainder of the month after my trial and error controlling pests, I kept busy clearing and thinning leaf canopy understories, in combination with removing vine laterals. I also needed to remove grape clusters. Most of my vines are in their third season. Limiting clusters to one per vine shoot is recommended since this continues to push the vine to root development versus grape development. Older vines are typically pruned to two clusters per shoot. I find it exceptionally heartbreaking removing the beautiful excess clusters but I must knuckle under. I may have made a rookie mistake removing too much of the leaf canopy understory in several spots putting the grapes at risk of sunburn but remember, this is a learning journey.

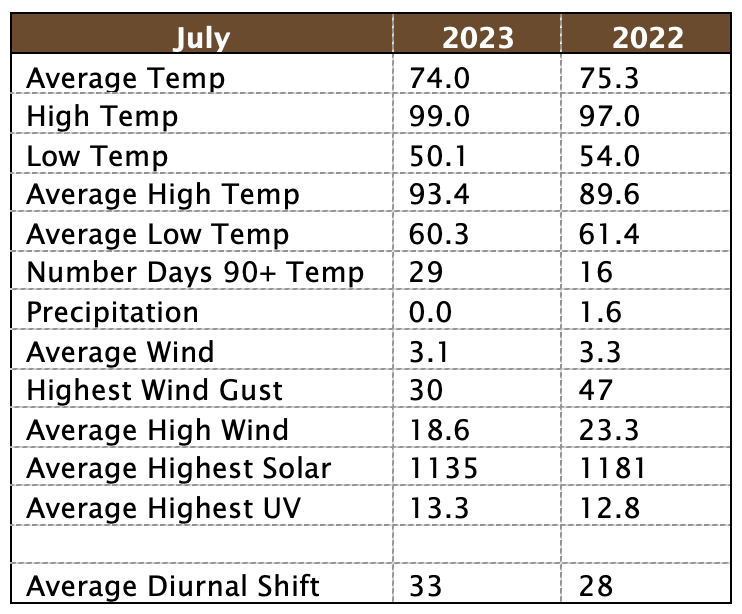

We can’t leave July without the monthly weather report. A neighbor friend who is a long-time Valley resident recently commented to me how exceedingly warm it had been. My default for hot summers is consistent upper 90s, interspersed with a few 100+ temps. Sure we’ve had a few hot days but our highest temp to date had been 99, the mid-90s had been more common. So being curious I asked why he thought it had been so warm. His answer was consecutive 90+ degree days and higher than normal nighttime lows. He didn’t have anything to confirm his observation. Being a data geek and in possession of a weather station, I decided to check.

As it turns out, my friend sans data was mostly correct. Not only had my vineyard experienced 29 days of temps above 90 but they were consecutive, running from July 1 (the first 90+ degree temp of the season) to July 29. While not reflected in the table, 90+ temps in July 2022 were less consecutive. The 2023 average low was 1.1 degrees lower than 2022, a minor difference. The 2023 average high temp was higher by 3.8 degrees, a more significant difference.

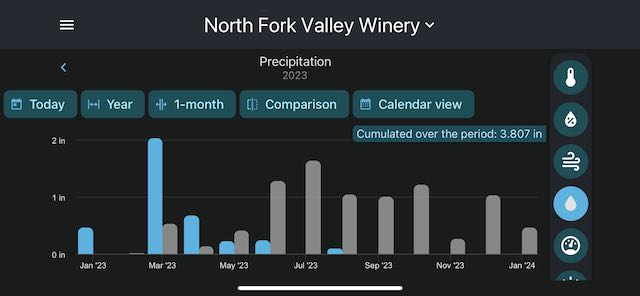

One other weather item not discussed with my neighbor represented by the graph below (gray bars 2022, blue 2023), 1.6 inches of rain in July 2022 was the start of last year’s monsoon season. Precipitation remained fairly consistent for the remainder of 2022, extending through mid-May 2023—when the moisture spigot turned off. As of the end of July, the monsoon hadn’t yet begun in western Colorado though it was in full swing in eastern Colorado and Denver.

Moving forward, I’ll be reporting weather data using the format presented in the table. I only have two years’ worth of data so in future years, the table will have additional columns for each year. Graphing the annual differences should be instructive.

The table contains three unique measurement items I like to track to the vineyard. A diurnal shift is the difference between the average high and low temps. It is important in viticulture because large diurnal shifts promote balance between the acidity and sugar in the grapes, producing better quality wines. While above 30 is good, several well-known grape and wine-producing areas can experience upwards of 35 to 40-degree shifts. The Ultraviolet (UV) index, measures levels of UV from the sun, indicating the need for sun protection measures. Readings above five are high, and 11+ is extreme. In western Colorado at our higher elevations average UV highs are almost always in the extreme. A probable need to provide some level of leaf protection for maturing grapes. Solar radiation is a similar measurement, which can be expressed in watts per square meter for solar electric (photovoltaic) systems.

As the month ended, I had one Pinot Noir vine showing veraison, the turning of color in the grapes. Veraison is a pivotable milestone in a grape’s lifecycle, indicating an upward swing of sweetness. This is the last developmental stage before ultimate sweetness is achieved for harvest and winemaking. Does this one vine represent a “false” veraison, or is it illustrative of what is about to take over the vineyard the first few days of August? Time and the August Chronicles will tell the tale!