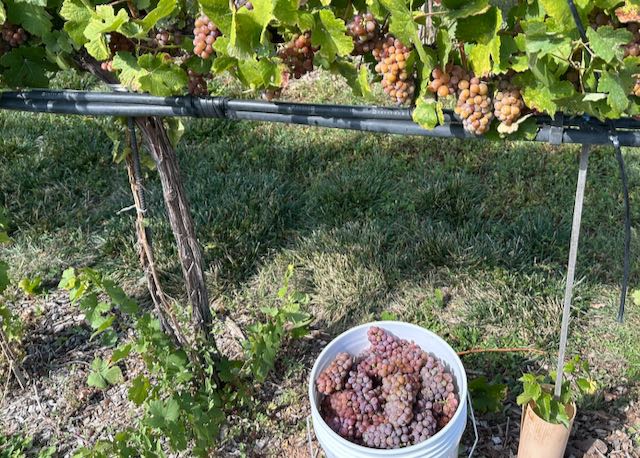

2025 - Abundant Grape Harvest

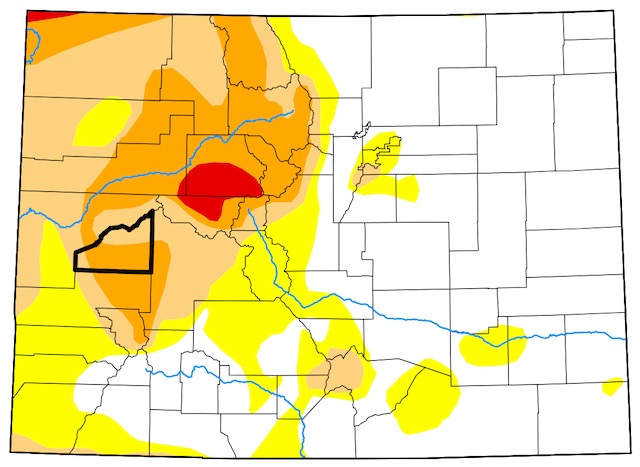

Drought Conditions Persist at Lower Levels | Yellow Jackets Back

"They keep me company and in return I feed them."

The Author's quip after another afternoon spent with Yellow Jackets

It’s been a great season for my vineyard, resulting in an abundant grape harvest.

Vineyard threats, including fungal diseases, insects, birds, and mammals, were tamed and minimized. The weather was consistently hot, but not excessively so. We experienced extreme drought conditions in the first half of the year, which lessened in August, September, and October.

A combination of these circumstances, coupled with a higher percentage of four- and five-year-old vines in my vineyard, resulted in the largest grape harvest yet.

Of my 125 vines, two-thirds are Pinot Noir, and the remaining are Riesling. The Pinot provided 350 pounds of grapes, while the Riesling gave 125. This compares to 150 Pinot pounds last year, and 110 of Riesling.

Added to the harvest, additional grapes were obtained from a local grower friend, consisting of 125 pounds of lower-Brix (sugar) Pinot Noir for a Rosé, and 125 pounds of Gewürztraminer, now blended with my Riesling.

After crushing, destemming, and fermenting the grapes, the winery produced 33 gallons of wine, which equates to 145 bottles or 12 cases. The calculation is based on bottling 29 gallons, because a certain level of wine is lost through racking (moving wine from one vessel to another, leaving behind the settling sediment), and bottling.

Season’s Challenges and Advantages

Much of this year’s successes were a result of applying solutions to lessons learned from previous seasons, combined with a bit of luck.

For example, I often sprayed for fungal diseases such as powdery mildew and for insects, including leaf hoppers and grasshoppers.

I was ready with a raccoon trap in case they showed up. Fortunately, they didn’t until after the harvest.

The preponderance and timing of high spring winds weren’t as bad as last year. Il-timed high winds in the spring can trigger flower shatter, which can strip away developing flowers. Since flowers produce grapes, flower shatter compromises grape clusters, reducing their quality and quantity.

But don’t kid yourself, the season wasn’t all unicorns and ponies.

First up, the drought in western Colorado. As reported in my July post “A Midsummer Night’s Dream – Moisture”, we were in the middle of an extreme drought. According to my weather station, there had been only 1.88 inches of rain through July.

Essential to point out, a drought doesn’t negatively affect my vine and grape growth. The vines are drip irrigated, compliment of a reliable spring. In addition, there is a positive benefit to the dryness. Powdery mildew is easier to control because it primarily grows and spreads in wet conditions among vines and grapes.

However, on the downside, the drought has a negative impact on the valley and western Colorado more broadly, as irrigation water from ditches, springs, and ponds becomes increasingly scarce. Case in point, several ditch companies turned off their water weeks early due to the dry conditions.

Another unfortunate byproduct is wildfires. Also reported in my July post were the manifestations of several fires, which luckily were tamed by early August.

Second up, my old 2023 yellow jacket nemesis made a comeback (August 2023 post “the Apocalypse”). In 2024, I deployed yellow jacket traps in early April, which caught many famished queens emerging from their winter nests. In theory, the result is fewer queens, fewer nests, and fewer workers accosting the grapes.

The theory worked, or so I thought. I rarely came across a yellow jacket in 2024.

For some unknown reason, this year, applying the same approach did not catch many queens. I reckoned the previous season’s queen eradication had had a lasting effect. Not so much as it turns out. Research has shown that diminished food sources due to drought are a primary driver of hungry, aggressive yellow jackets. Nicely coined by the word “hangry”.

And brother, were they ever hangry this season.

Talking with my wine-growing and winemaking neighbors across the way at The Storm Cellar revealed they faced the same hangry dilemma. Other growers in the valley didn’t to the same degree.

Mother Nature mysteries abound!

Luckily, I saw the handwriting on the wall in early August. The was a preponderance of yellow jacket activity at the traps. At the same time, a fortuitous email hit my inbox hawking discounted bee netting. Or, in other words, yellow jacket netting. Compared to the bird netting I use, the netting weave is much finer, restricting both birds and insects. Within 5 days, the new netting arrived. I began immediate deployment.

Crises averted.

It is important to note that the insect netting wasn’t foolproof. I used side-netting, which, as the name implies, only protects the sides of the vines where the grapes are. Small open slits are left when clasping the nets around vine trunks at the bottom and canes with leaves at the top. This allows a few industrious yellow jackets to enter the grape zone. I also witnessed a few diligent characters broach the weave.

For a more foolproof, commonly used approach among commercial growers, over-the-top netting provides 100% vine coverage. Unfortunately, this isn’t a viable approach for me, due to the challenge in deploying the wider nets in my one-man viticultural operation.

Bottom line, the netting still did its job and yellow jacket damage was kept to a minimum.

Third and last up, honorable mention goes to grasshoppers. The past two seasons, they’ve been a real bother, eating away at vine leaf canopies and new growth. As an experiment, in early June, I began applying two different sprays to control them. First, a combined solution of two organic products was sprayed on the vines. One product is Pyganic, which slowly kills via contact after a day or two, and the other is Venerate, which kills upon digestion. The second product, the non-organic Talstar, was applied outside the vineyard boundaries in adjacent fields where grasshoppers were abundant. This solution kills by contact and digestion, and it stays active on vegetation for 90 days after application. Talstar shouldn’t, and wasn’t, applied on the vines.

This new approach worked in spades.

There were a few grasshoppers on the vines, but in low numbers. They were easy to remove by hand and could even be ignored.

New Vineyard Endeavor in 2025 and 2026

A curious reader might ask whether there were new challenges this year that required creative problem-solving?

In a way, there was one. The wire trellis that supports the vines.

There are eleven rows in my vineyard. The rows have metal end-posts, pounded into the ground. Over four years of supporting heavy vine canopies, many posts were loosening. It was nearly impossible to keep the trellis wires taut. Determined to correct the situation this year, I reset approximately half the vineyard’s end-posts in concrete, believing this would solve the problem.

It worked, but there were issues. In some rows, the concrete didn’t hold as well as I hoped, and in several cases, the metal posts bent under tension.

Really?

I’m thinking through end-post remedies for next season, which I’ll delve into more deeply in the third annual edition of my “Lessons Learned” post later in the year.

Always something to problem-solve and learn. Stay tuned.

As your somewhat conferee in vino production, your efforts to grow grapes in the high desert are great, and the challenges that continually arise always keep one on his(her) constant alert mode. Our vines may not look picture perfect, like some places in the US, but that is not the point. As you are now traveling around the world and discovering, those old vines , crooked, deformed, absolutely beautiful, make wonderful vino, no matter the “perfect” look. BTW did you have an opportunity to enjoy a bit of Barbi Nicole’s Champagne? She certainly did change the world of Champagne making as well as the distribution of same. Be well and keep up your Blog, and safe travels….OG(Opera Ghost)

Your points are well taken, and as always, I appreciate your insights. Oh, I did take the opportunity to enjoy Barbi Nicole’s Champagne, and have lunch as well!